I have to admit: before making the effort to delve into the depths of Philippine Martial Law history available to us via multiple platforms (books, movies, the internet), I was one of the sadly mistaken millennials who fell for the Marcos loyalist propaganda on my Facebook timeline. In light of recent events, I’ve began to realize how truly important it is to have a uniform educational standard for each Filipino citizen—the fact that we had the son of a dictator, Bongbong Marcos, fighting neck and neck for the second-highest position in the country is troubling in general. It made me think about how our education system has failed us and how we haven’t been properly educated on the actuality and aftermath of those years. Perhaps we owe the widespread misinformation to the fact that there is no uniform standard on what is to be taught about martial law, thus resulting in some schools teaching anti-Marcos/pro-Aquino and others teaching pro-Marcos/anti-Aquino, but none who provide unbiased, impartial, and complete recounts of what happened then. Of course, this and the fact that others rely only on hearsay provided by family members—not to say that our families are liars, but we must face the irrefutable fact that aside from the elite that lived in comfort then, many people outside of their circles suffered under the hands of the Marcos administration. It just makes you wonder: what is the value of your comfort and security if it’s at the expense of others or means that others are unjustly persecuted?

To every active netizen of the Philippines, it is known that martial law has once more become the center of many heated discussions. Those who have lived through that era or those whose families were victimized walk around with question marks above their heads, questioning the sanity of the little over 14 million people who voted for the only son of Ferdinand Marcos. Many seem to think that it’s because 75% (20 million) of the registered voters were millennials, people aged 18-35 who coincidentally don’t know what it was like to live under the Marcoses. “Tinutulugan ang Hekasi, pero nagpapadala sa Facebook propaganda [sleeps in civics/world history class, but believes in Facebook propaganda],” an angry netizen said. While I heartily dislike how our elders stereotype millennials as “miseducated and misinformed” about martial law, I can’t help but agree. While not all of us are ignorant to the heinous atrocities committed then, a great majority of us seem to have become apologists, who for some reason or the other try to defend the Marcoses. While yes, we didn’t live through that time period (and therefore cannot fully conclude whether or not it was a good time to be alive), there are more than enough sources available to us that should—at the very least—prove to us that it was no time of gold (except for the gold their family stole). Here, I contest some of the most common myths and arguments perpetuated by loyalists/apologists:

“The Philippines was economically prosperous and progressive!”

A lot of talk about how the Philippine peso and the US dollar were basically on equal footing usually comes in when it comes to this. It is a common misconception to believe that near-equal dollar exchange rate is synonymous to economic prosperity—take a look at Japan, for example. Something that we have to remember is that prior to the Marcos rule, Diosdado Macapagal already had the peso at P3.70 to a dollar and sunk it to P4 to P6 by the end of his term. In Marcos’ time, the exchange rate was at P3.70, which by the time martial law was lifted turned into P20:$1 (not to say that any of the succeeding presidents did any better). In addition to that, the wealth was distributed unevenly between the different classes—the poorest 60% of the nation only received 22.5% of the income in 1980 from the previous 25% in 1970, and the richest 10% of the country received 41.7% of the country’s wealth—up 10% from its original 31.7% in 1970. The unemployment rate (from 5.2% to 5.9%) and the underemployment rate (10.2% to 29%) rose tragically, thus leaving the country with a poverty incidence of 42% (meaning that these people lived below the poverty line). Some also dare mention the infrastructure erected in the time of ML, claiming that if Marcos had stayed in office, the debt created by constructing these would have been paid. But the sad truth about it is that it’s extremely easy to create roads and other infrastructural programs when you’ve abolished congress and have had 21 years in office to do so. And the debt? It wouldn’t have paid itself off. The construction of infrastructure creates a only a temporary boost of the economy. By the time Marcos was unseated, the Philippines’ debt had reached US$ 28 BILLION. This means that our taxes will be paying the Marcos debts until 2025.

“Martial Law instilled discipline and order throughout the country!”

Tell that to 23 year-old college senior Liliosa Hilao, considered the first casualty of martial law. Drunken soldiers barged into her house, raiding it and looking for her brother. A student activist, Liliosa demanded a search warrant. The soldiers detained her and when her sister answered to a call by the hospital the next day, she was dead. Her cause of death was ruled as suicide, but post-mortem examination reports state that she had cigarette burns on her lips, 11 injection marks in her arm, deep handcuff marks on her wrist, and showed possible signs of sexual abuse. Tell that to Boyet Mijares, son of author Primitivo Mijares, who answered to an anonymous call saying his father was alive and wanted to meet him. Weeks later, his body was found dumped along the outskirts of Manila, his head bashed in, chest perforated with stab wounds, eyeballs protruding, genitals, hands, and feet mangled. These are just two of the hundreds of thousands of reported deaths in the 21-year martial law era—Amnesty International reports a total of 70,000 jailed; 34,000 tortured; 3,240 killed, and that’s only the reported deaths. What more if we tally the ones that were never recorded? Those who were detained were subject to unrelenting torture methods, some of which included electric shock, water torture, sexual violence, russian roulette, and more. Today, we get angry at people who suppress our internet freedom; we love staying out at all hours of the night; we love having the freedom to unapologetically be ourselves, and that’s something that we wouldn’t be able to do then without getting detained or dying. We wouldn’t be able to speak about the government as we do, so critically bashing the administration. We wouldn’t be able to go drinking, smoke, or most especially go home late. And for those whose dreams include being writers, our only editors would be the government, and once we say something wrong—goodbye. Something that the current Prime Minister of Canada, Justin Trudeau once said applies to what many say is the “most disciplined era” of our nation: “If we allow politicians to succeed by scaring people, we don’t actually end up any safer. Fear doesn’t make us safer, it makes us weaker.”

“Ninoy and Macoy were friends, the Aquinos are traitors!”

Now, the first thing I’d like to say is that to be anti-Marcos isn’t synonymous to being pro-Aquino. In fact, many of those who oppose the Marcos regime are also well-aware of the sins of the Aquinos, as well. This includes the Mendiola Massacre of 1983, Hacienda Luisita of 2004, and the most recent Kidapawan just last April. Though admittedly, some have bordered close to glorifying them when it comes to the liberation from martial law, leading others to believe that this was purely an Aquino vs. Marcos thing. In reality, the death of Ninoy Aquino was only one of thousands—though, undeniably can be considered a catalyst in the movement for freedom. When Corazon Aquino (Ninoy’s widower) became the face of the revolution, every citizen screaming freedom wanted her in the highest seat and not Marcos—a choice many came to regret after the economy sank even lower during her term. After all, she did jump from housewife to president, so she had a vast cabinet of advisers. When we look at martial law as something purely Aquino vs. Marcos, we forget and invalidate the victims who were merely students, fighting for what was right; journalists, who were just doing their jobs; civilians, who were just trying to live. When we look at martial law as something purely Aquino vs. Marcos, we close our eyes to the blood spilled that wrote the history and built the foundation on which we stand today. How come children know about People Power and Ninoy’s assassination, but not the innocents who perished? Simple—it goes back to the miseducation. People often rebut that though the Marcoses weren’t the best, neither were the Aquinos. And yes, we acknowledge this, but the fact that the Aquinos were bad doesn’t overshadow how cruel the Marcoses were to impose such horrors on their own countrymen. We shouldn’t undermine the gravity of a significant period in history by bringing to light another equal terror, because they are both equally significant in their own ways.

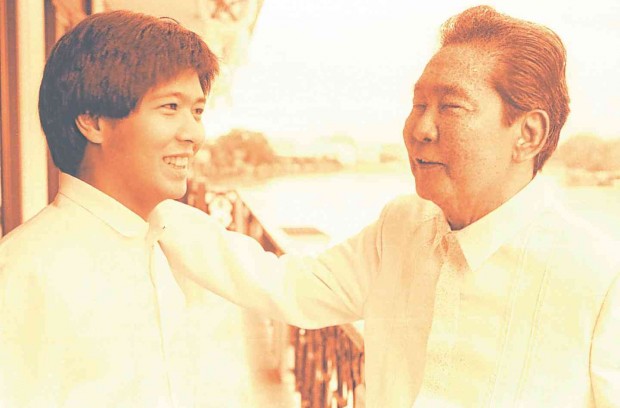

“Bongbong isn’t his father!”

Ah, yes. The classic “the sins of the father are not the sins of the son” argument. While I do agree with said statement, it brings me to this: isn’t turning a blind eye to all the injustice committed before your very eyes not an injustice in itself? After all, if you don’t help the oppressed, then you empower the oppressor. And who said that Bongbong was innocent during these times? Bongbong was in his twenties and very much active in the regime of his father. Bongbong was appointed the chairman of Philcomsat as early as 1985, earning a salary of at least $9,700 a month even with no office duties. Other than that, he was appointed as the Vice Governor of their home province Ilocos, and during the time of the famed EDSA Revolution, was uniformed and ready to combat the peaceful protesters. Moreover, after their exile to Hawaii, he was tasked to keep in constant contact with Credit Suisse—which held all of the plundered money. And if that wasn’t enough, he refuses to apologize to or even just acknowledge the victims of their regime. He claims that he cannot apologize for anything that happened then. And if it still isn’t enough, outside of his sins relating to his father, Bongbong and his family are still in possession of the billions taken from the Filipino people then. Declared as the richest vice-presidential candidate, Bongbong filed a petition to stop the Philippine government from getting back the remaining half of the over $10 billion of the ill-gotten wealth. And most recently, the prestigious Oxford University has disproved the senator’s claims that he earned a diploma in political science there. So what has Bongbong done? If the sins of the father aren’t of the son’s, the most certainly the achievements of the father’s aren’t the son’s, either.

It is not entirely that Bongbong will impose martial law if elected, but rather what his family name means to thousands of surviving victims and the surviving families of dead or lost martial law victims. We mustn’t push aside our history—after all, great countries such as Germany rise from the horrors of their past by coming to terms with it, educating their young, and learning from their past. It isn’t something that we can simply “move on” from, especially considering the fact that we haven’t even received an apology from them. Especially since they haven’t returned the money that rightfully belongs to our country. Martial law will forever be a relevant time period as it heavily shaped what has become of our country today. By falling for the widespread misconceptions and misinformation, we put ourselves and the future generations at risk of forgetting what actually happened. We are going to be the ones responsible for educating our children about what happened in those times—we must learn to be able to tell the stories with complete truth and no bias, not swaying in favor to the red or to the yellow, but to recount the vicious injustices inflicted upon us not by foreigners, but by our own kind. We are responsible for how the next generations view and learn from martial law. Not only should we do this for the sake of the future, but to honor both the glorified and unsung heroes who fought for the kind of liberty we have today. Let us not walk back into the appalling tyranny the so fiercely fought against—let us value their sacrifices by never forgetting and never repeating.

After all, we only ever pave the path to a bright future not by forgetting the past, but rather learning from it and not doing it again.