Fifty years ago, the United States was shrouded by a storm of inequality so dense that even the police force actively partook in the crimes against the very people it was their duty to protect. However, the passing of time does not necessarily equate to progress being made, and we soon find ourselves questioning how different the situation today actually is.

Picture the following: peaceful protestors demanding their lawful rights. Maybe they’re only campaigning for the very right to live in safety. The police intervene. There’s tear gas. Batons. Blood. Is this a protest from the 1960s you are imagining? Or one from the twenty-first century? Harrowing as the situation described may be, the realisation that it is applicable to both time periods is even more terrifying. Has there really been no progress at all, and if so– why? In order to fully understand and evaluate any progress or hindrances that may have occurred, we must first examine the parallels of both eras, looking at the mistakes of the past as a guide to writing our future. While it is certainly true that American citizens of all races and cultures are now ensured every lawful right they deserve, the reality remains very different. Facts state that there are more than 1,100 police killings a year, which roughly– and quite shockingly– equates to one every eight hours.

The general trend of police brutality cases has remained constant throughout the years, especially with regard to the methods through which policemen attempt to deal with peaceful protests. Throughout the 1960s, it was incredibly frequent for policemen to use unnecessary, and often dangerous, means such as unleashing police dogs, spraying teargas, and blasting protestors with fire hoses during peaceful marches irregardless of their age. The scale of law enforcers’ leniency towards violence against black men was shown through just how widely it was known that Birmingham’s notorious police chief Eugene “Bull” Connor even permitted the beating of the Freedom Riders by a mob of Ku Klux Klan members for a full period of fifteen minutes, who were then able to walk away unscathed from the crimes they committed.

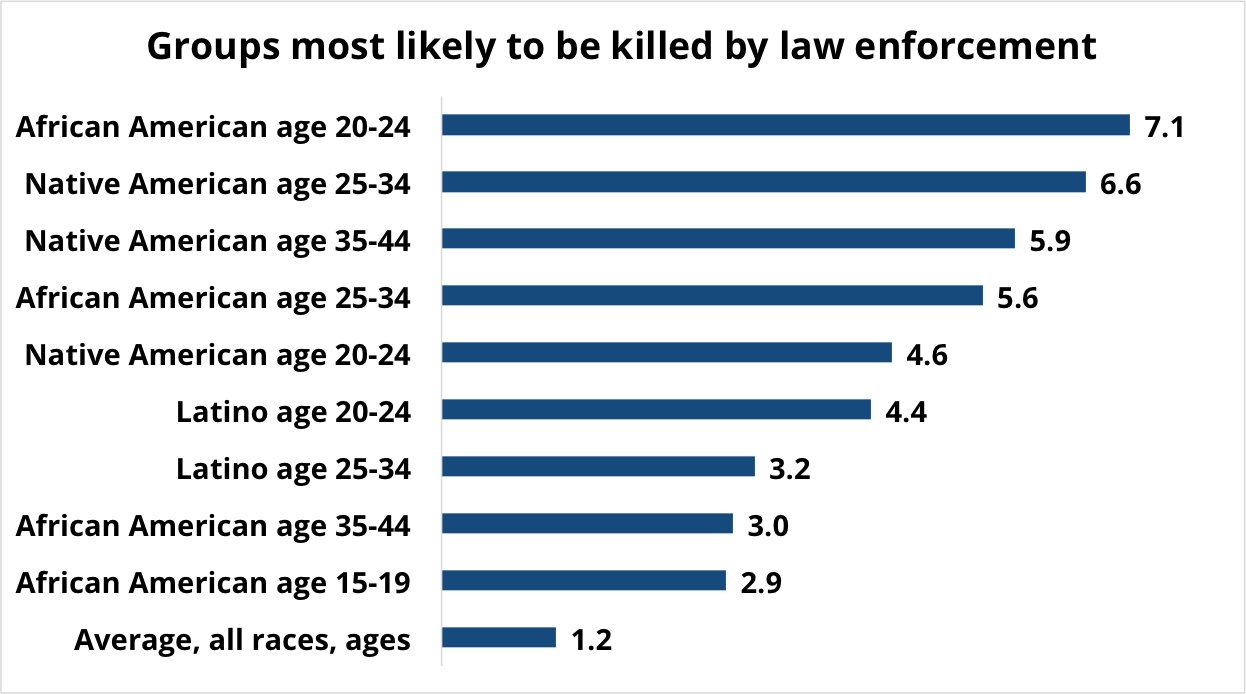

Fast-forward to 2016, where most police attempts at ending Black Lives Matter protests, such as the one in Phoenix this July, involve spraying crowds with tear gas and pepper spray. There are even recent protests also facing teargas sprayings that were completely uncalled for, such as at Standing Rock where Native American protestors trying to protect their sacred land have only just emerged victorious. However, police brutality is not only present in the context of protests – it is all around us in everyday life. Turning to more concrete evidence in the form of statistics, we can learn that every year throughout the late 1960s, almost 100 black men below the age 25 were murdered by law enforcement officers.

While today that proportion has certainly decreased, one-tenth of police-related killings are still black men under the age of 25, many of which were completely unarmed and therefore not even a threat. Many think that the fact that the number has declined means that the problem is no longer present when in reality, so much has yet to be done for it to ever happen. In reality, the rate of police brutality exclusively towards young black men only dropped by 15% – the issue at hand is still very much present. Amongst the victims are Rodney King, Tamir Rice, and countless others whose whole lives and futures were stolen away from them and their families by a police officer who did not bother to look twice before shooting. Now that we have established a general outline of the more superficial comparisons between the past and present of police brutality, we can move onto the next question: why is it that this is happening in the first place?

When answering this question, it is evident that this is not something that just comes down to an individual’s own racist attitudes. Instead, it is a part of something much larger – police brutality exists as a collection of actions: the system of recurring police corruption and misconduct. The real answer lies in the culture of impunity that exists in the America of today. The broken system the nation was built upon still remains along with state governments being given too much power as part of the 10th Amendment, allowing their full control of the state’s police force.

Evidently, a nation rooted in a system of slavery and the criminilisation of immigrants and people of colour is not a nation that will intently prosecute police officers for their crimes if the victim was coloured– especially if it is in the states’ hands to decide. Countless examples exist, such as how Eric Garner’s murderer, New York police officer Daneil Pantaleo was not charged for the crime he had committed. Knowing that they will not be automatically prosecuted means that there is no form of deterrence for police officers’ abundance of power to get out of hand, resulting in disastrous consequences.

An absence of clear policies on the use of force within police departments only heightens this, as the regulations that exist are really the bare minimum. The lack of disciplinary action paves the way for many acts of police brutality of varying degrees, which the very same police forces later try to cover up, with the federal government unable to do anything that could discourage police officers from acting out of line.

Worse still is how this has somehow become normalised, with the police continuing to use excessive amount of force in their work, without change. Suddenly we are thrust back into the 1960s, where justice would only be served if it involved a white victim while noses were frequently turned against any crimes that involved anyone else. Looking back at the aforementioned “Bull” Connor case, it is unfortunate, yet not surprising, that he managed to get away with his constant approval of the use of brute force, which even included unleashing police dogs on child protestors.

Taking a step even further back into history, the origins of black criminilisation that seemingly justified the frequent persecution of young black men by the police force can be identified. It is no coincidence that young black men have always been the group most targeted and killed by police officers. In the aftermath of the abolishment of slavery, southern states were desperate to instill anything that could essentially restore slavery in all but name. A loophole in the 13th Amendment allowed criminals to serve as slaves for their punishment, prompting black men to be criminalised even more than they already were, leading to a huge increase in arrests over the smallest of crimes– some of them even made up. Using black criminilisation, even more arrests were carried out, and then these arrests themselves were used as justification for the subsequent arrests, creating a vicious cycle of injustice. The corrupted state governments that once sold actual men to private companies for their own financial gain through a system of involuntary servitude are now the same states that continue their ridiculous tradition of black criminalisation. In the present day, however, this results in either mass incarceration or police brutality, which often come hand-in-hand as demonstrated in last year’s tragic case of Sandra Bland, which began an online movement.

“Just because there are now more eyes watching, it does not necessarily mean that there are more hands helping.”

In addition, some may argue that the one factor that is actually different this time around is the introduction of technology and the way it has found its way to incorporate itself into the situation, effectively moulding the movement against police brutality. Attacks can now be recorded and monitored by both governments and the general public, increasing the global exposure over this alarming issue, and thus increasing the international pressure on the American government to do something in response. However, the United States was already experiencing serious national and international shame for certain cases of police brutality. Although not explicitly committed by policemen, the murder of Emmett Till in 1955 was, in its nature, quite similar to modern cases of black teenage murder victims. Emmett was only fourteen when he was murdered on the grounds of supposedly flirting with a woman. However, his case received large amounts of exposure and heavy criticism in the media, much like the modern day cases. Thus, it potentially demonstrated that more exposure really does not solve anything. Just because there are now more eyes watching, it does not necessarily mean that there are more hands helping. This undermines the possibility that there has been some major improvement in American police brutality, both in respect of gaining more exposure, and this exposure actually being beneficial.

To conclude, it can be agreed that the reason for the prolonged continuation of police brutality lies in the impunity that police officers have been relishing in for far too long. Ultimately, it can only be hoped that sometime in the near future, the United States will finally overcome the offense that is police brutality by dismantling this culture of impunity piece by piece. A future with an entirely reformed, improved system may seem unlikely now, but it is certainly a very viable possibility if campaigned for. Beginning with making police brutality and misconduct a federal crime, and fully enforcing this whenever required, the whole system can then be challenged. By continuing to shed a spotlight on this issue– through protests, signing petitions and frequent discussion of the relevancy of this matter through social media, word of mouth, or articles such as this one– we can only hope for a better future where a whole past of suffering is not in vain and can be finally used to learn something. Nevertheless, it is still a shame that ‘the Land of the Free’ is still considering whether the people of one of its largest racial demographics have the right to live feeling protected, rather than persecuted.