Late last year, on September 29, Austrian adults headed to the voting booths. With them went many members of a globally unusual cohort: 16- and 17-year-olds with voting rights.

Since the European country lowered its minimum voting age in 2007, anyone 16-years-old and over has been able to vote in both the presidential and legislative elections. And while Austria is an anomaly in that respect, other countries like Brazil, Malta, Scotland and Argentina also share comparatively low minimum voting ages. In each of these countries, you can vote as soon as you turn 16.

In the United States, in line with most major democracies, the voting age is 18. The same goes for Australia, New Zealand and Britain. Public opinion is also squarely in favour of that remaining the case. In 2019, a Hill-HarrisX poll found that 75 per cent of registered voters opposed letting 17-year-olds vote, and 84 per cent opposed it for 16-year-olds.

So why did Austria go ahead with the change? And why have calls for lowering the voting age in other democracies grown in recent years? In Austria, the 2007 change was bundled up with a sweeping electoral reform package – and came as part of a coalition exchange of reform policies. The conservative ÖVP party wanted absentee ballot reform, and the left-wing Social Democratic Party wanted lower voting ages. The big reason calls to lower the minimum age have increased globally recently is building youth political involvement, as evidenced in the School Strike For Climate protests, racial justice movements or the high school shooting outcry. Young activists – from the Vietnam war generation – used to be college students. Now, they skip high school to protest.

Adding to that is a growing realisation that ageing populations in many western democracies tend to skew the political power in favour of the old. This is problematic when the elderly have very different priorities to young people; issues like climate change, education and adorable housing may not get the attention they deserve.

Other arguments have been around for longer. Lowering the voting age sparks interest in the political process at a younger age, creating habitual voters. “By lowering the voting age, people are dealing with the political landscape at an earlier stage. At the same time, more investment is being made in political education,” Tamara Ehs, chairwoman of the Austrian interest group “IG Demokratie”, told Euro News. “Thus a political anchor is set among the young citizens,” she said.

On the opposing side, critics raise issues such as lacking mental development, or an absence of knowledge around how a government actually works. Here’s an example: In Australia, since 2004, a group called the National Assessment Program on Civics and Citizens has measured student’s level of knowledge about the Australian Government, judiciary and democratic processes. The 2016 version report showed a consistent decline in proficiency, and only 38% per cent of Year 10 students achieved at or above the standard, a continuing trend from 2010. Another widespread counter-argument is that, at 16, teens simply don’t have enough skin in the game of life. Opponents stress that teens aged 16 don’t pay taxes, and don’t own houses. (This is not, in the former case, true: Anyone earning upwards of $12,400 in America in 2020 had to file a tax return, regardless of age. Around 35% of teenage Americans had jobs, in 2019.)

The problem is, lowering voting ages comes with a catch: teens just don’t turn out to vote like their parents and grandparents do. In New Zealand, for example, during the 2017 election, there was lots of talk about a supposed “youthquake.” That is, a wave of young people turning 18 and swinging the vote in the favour of progressive candidates. That youthquake never materialised, and even this coming election, only about 60% of those aged-18 to 24 are registered to vote. This usually has consequences for the left. In New Zealand, prominent right-wing commentator Mike Hosking has warned that low voter turnout among 18-year-olds could cost the Labour party its a bigger winning margin.

Proponents say that lowering voting ages successfully has to go hand in hand with a bigger focus on political education in schools. Civic education, as it’s often called, would outline to school leavers how to vote analytically, its importance, and how to register in the first place. Teens have complained that, even in Austria, education in schools on the voting process is lacking. In countries with higher voting ages, that criticism is maintained. “If civics education is too important to be left to chance, perhaps it is time to formulate a universal curriculum core,” Mike Taylor, from Victoria’s Faculty of Education, has written.

In 2020, it’s been over a decade since Austria let 16-year-olds vote. How has it turned out? Well, a Fortnite party hasn’t been elected yet. According to Sylvia Kritzinger, a professor at the Institute of Political Science at the University of Vienna who spoke to Euro News, allowing 16- and 17-year-olds to vote has actually been a way of increasing the youth voter turnout – which is great for the health of democracy. In other words, teens do vote, contrary to what critics of the change argued 10 years ago. This is because those in the 18-21-year-old group tend to be experiencing personal upheaval, moving out of their parents’ houses. 16 to 17-year-olds turn out in lower numbers than those over 30, but higher numbers than those in the 18-21 group.

Overall, there’s been little pushback to reverse that decision – and, recently in America and beyond, teen voting activists have been ramping up their calls for lowering the voting age. And with elections that’ll decide on issues as future-minded as the Covid-19 recovery, racial justice, gun rights, education, and our path to a more sustainable society coming up, expect those calls only to grow.

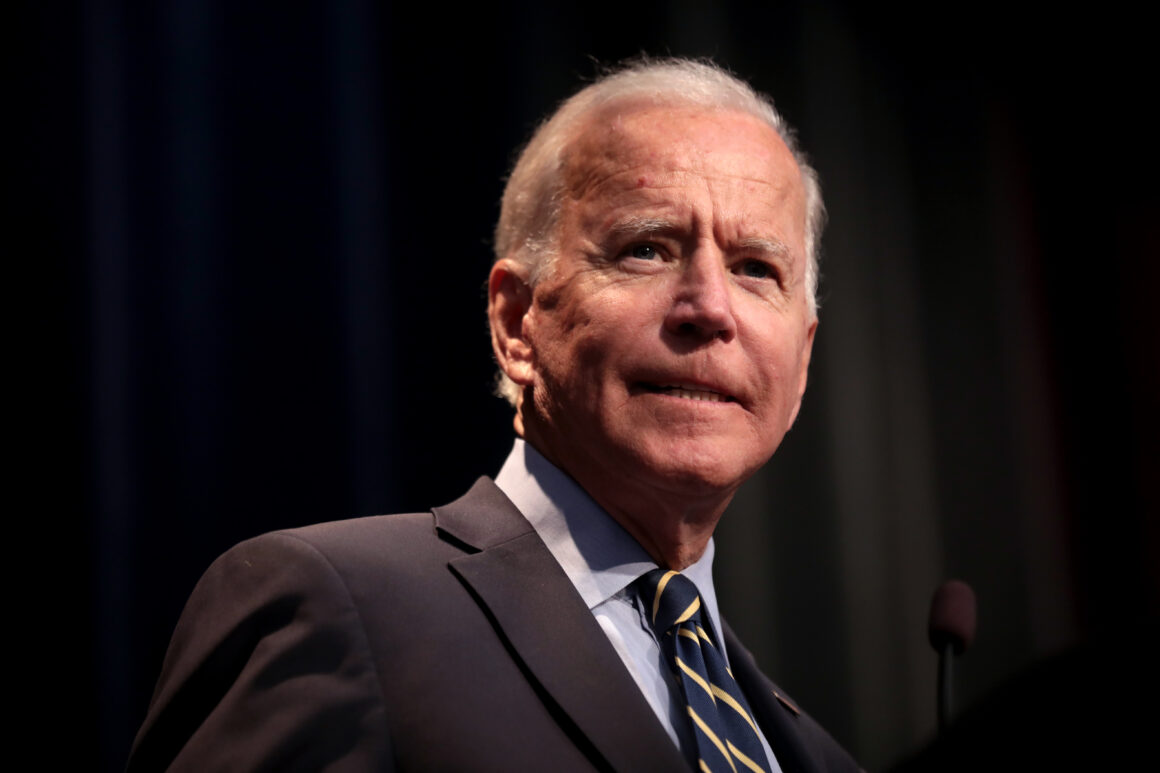

Featured image: Marco Verch