In the era of “fake news,” it seems the entire journalism industry has come under fire. Regardless of which side a source supports, it is apparent that world news dialect has been completely altered since the politics of yesteryear — or pre-2016, for that matter.

After gracing the pages of ancient Greek literature, this powerful rhetorical device has become a large facet of political vocabulary, though many lack an understanding of its foundation. It is the epithet– what Merriam-Webster dictionary describes as “a characterizing word or phrase accompanying or occurring in place of the name of a person or thing.” While that might surely describe Homeric epithets such as “famed Odysseus,” the second definition Merriam-Webster provides may be more suited to the current atmosphere. It reads: “a disparaging or abusive word or phrase.”

Sure, epithets have been used in campaigns and presidencies before– just think of “Honest Abe.” However, the uses of today hold a key difference to the glorifying epithets of Homer’s time: they are, beyond simply disparaging, factually irrelevant. Trump pioneered this on the campaign trail, calling his opponents “Crazy Bernie” Sanders, “Little Marco” Rubio, and even more prominently, “Crooked Hillary” Clinton. Even now, nicknames remain a function of his presidency, from coining Elizabeth Warren as “Pocahontas” to deeming North Korean leader, Kim Jong Un, “Little Rocket Man.” Homer’s epithets serve to remind readers throughout such length as a Greek epic of character traits, such as “bright-eyed Athena.” After characterization spanning thousands of years of Greek literature and mythology, said traits are taken as fact. Conversely, epithets of today have become speculative. After all, what gives one person the right to label another for appearance or on false psychological grounds, to besmirch their name publicly and unjustly?

Further, what is it that makes these epithets so damaging? To put it simply, it is because they are catchy. When blasted from a podium, they hand the audience a headline or sound byte: a much more tangible vessel of their unvoiced opinions. Once a nickname like “crooked” sticks, it can be easy to pass off as fact simply for the extent to which it is used.

Never before has the concept of “alternative fact” been a feature of world news. The oxymoronic term first arose in an interview between Chuck Todd and Kellyanne Conway, currently Counselor to the President. When prompted to explain former Press Secretary Sean Spicer’s defense of the president’s claims on his inaugural crowd size– which essentially focused Trump’s first presidential press conference on falsehood– Conway responded that Spicer had merely employed “alternative facts.” While different facts can absolutely support different viewpoints while remaining true, this description for something so quantifiable as crowd size demonstrates, in this instance, both that Spicer spoke of a provable falsehood and that Conway corrupted the term to regard such falsehood. No longer may “alternative fact” signify a different viewpoint; it now resounds as something which calls into question the entire institution of journalistic integrity. How, with such an excuse, can the country possibly move forward if it cannot even set a foundation as to what can be held as fact? How can a source prove itself to be more than “fake news” if it is opposed by unfounded claims, left defenseless by the distortion of the inherent definition of truth?

We find ourselves caught up in this question of integrity, in a question of how the progress of world news is and will continue to be altered. The current administration regards dissenting media as the “enemy of the American people,” yet the suppression and delegitimization of critical beliefs is exactly the point by which journalists are beginning to draw even further into comparisons in literature. Some go so far as to paint an Orwellian picture of today’s society. They outline “fake news” criticisms in the same light as “thought crimes,” and such world news rhetoric as a rapid progression toward “newspeak,” 1984’s language of deception and suppression of free speech. This dystopian generalization does not dictate the progress of modern society; however, it does highlight the idea that the most controversial events of our ever-changing world all lead back to our understanding of language — of our societal experiences through literature and the rhetoric that binds us.

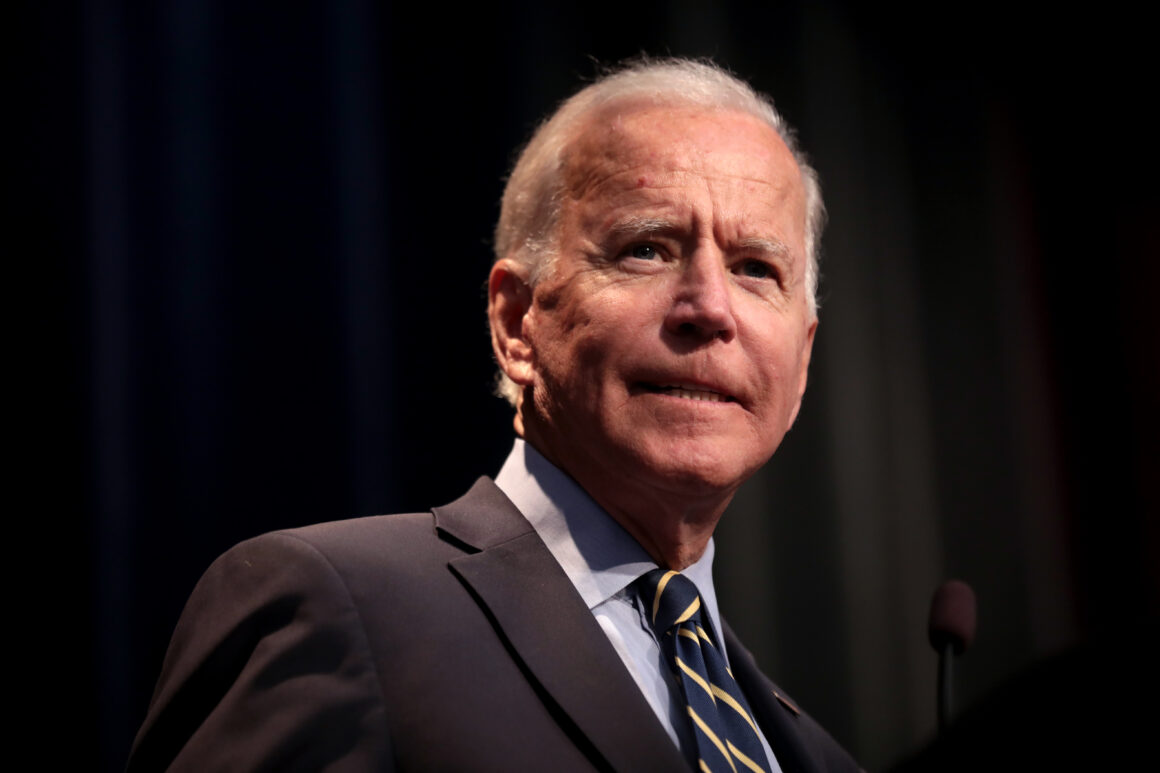

Photo courtesy of Jerry Kiesewetter on Unsplash