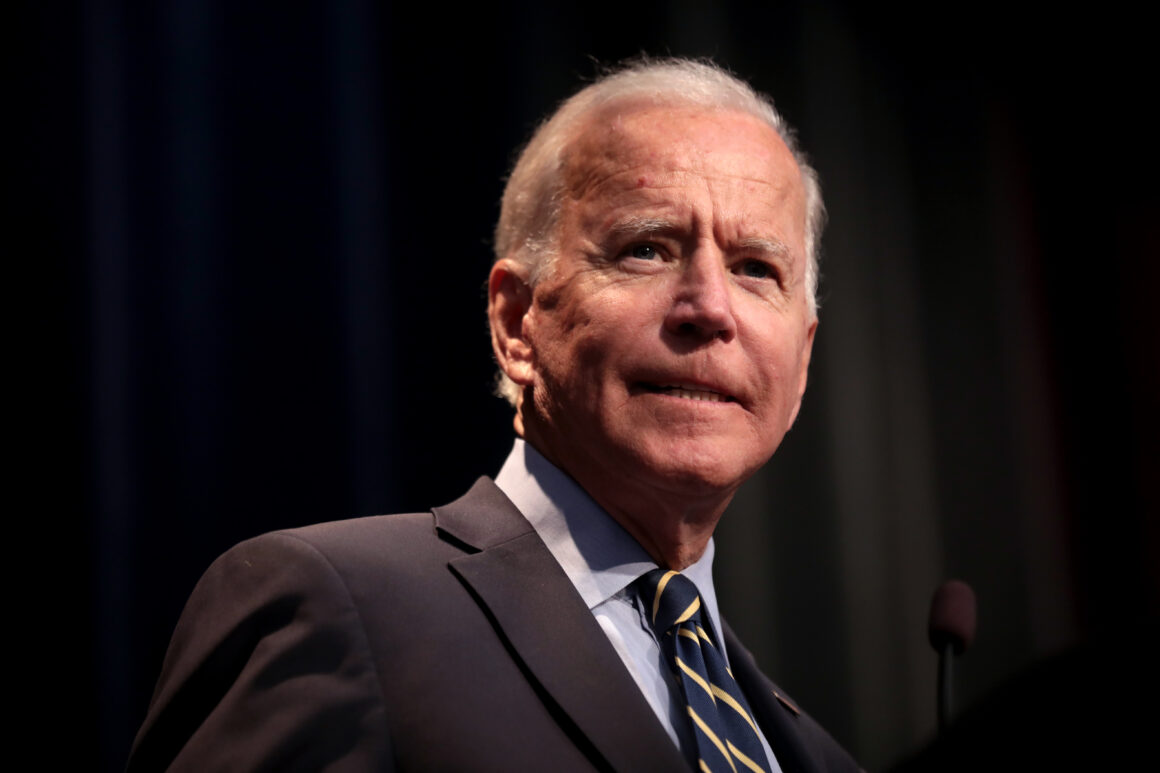

In September, Congress voted to reauthorize the Violence Against Women Act (VAWA) until Dec. 7 as part of a general spending bill, which left many domestic violence advocates concerned about the future of the act. VAWA was first proposed by former vice president Joe Biden in 1990, and the idea gained traction in the wake of the Anita Hill and Clarence Thomas hearings until it was successfully passed in 1994. It has been hailed as a major step forward for victims of intimate partner violence and other forms of abuse in the United States. However, the loss of this bill could be devastating, and many people do not realize it. Despite its association with a landmark sexual harassment case and years of improved conditions for abuse survivors, some still do not know exactly what VAWA symbolizes or what its potential absence will mean for survivors. Here is the breakdown.

Does VAWA outlaw domestic violence?

VAWA does not actually criminalize domestic violence, but rather encourages law enforcement and state legislators to take action against it and allocates the resources to do so. It provides funding to states for community-based programs to support those impacted by domestic violence, as well as preventive measures.

If the bill did not outlaw violence against women, then what did?

There were several legislative and judicial actions prior to the introduction of VAWA that provided protections against domestic violence: the first laws against physical abuse in the United States were passed in the 19th century as a response to the 1824 Supreme Court case Bradley vs Mississippi, and the 1986 case of Meritor Savings Bank vs Vinson declared sexual harassment a violation of the Civil Rights Act. VAWA, along with the Family Violence Prevention Services Act of 1994, simply strengthened these pre-existing protections.

Does VAWA only protect women?

In the original bill that was passed in 1994, yes. But as of the most recent reauthorization in 2013, protections have been expanded to include men, LGBT+ individuals, Native Americans (especially those who live on tribal lands, and thus, outside of federal jurisdiction), and immigrants. Women were the primary target of the bill because they constitute the majority of domestic violence victims, but if Congress allows this bill to lapse, it will ultimately impact more than just women.

Why does the bill need to be reauthorized in the first place?

As previously mentioned, VAWA allocates funds to state organizations and law enforcement to end domestic violence. Just this year, the state of Massachusetts received $12 million from the Office of Violence Against Women. Since the bill involves finances rather than just delineating punishments for domestic abuse, it has to be revisited on a regular basis. Katharine Baker, a professor at the Chicago-Kent College of Law, argues that the end of VAWA would have “primarily financial implications,” as several states use funds from VAWA to prosecute abusers, and successful prosecution has an impact on how society reacts to domestic violence.

Why is the bill important?

Even with VAWA in place, there is still a shortage of resources to support survivors. Despite providing more resources for states to prosecute perpetrators of abuse and guidelines to ensure justice is served, many abusers still get away with their crimes, and situations of domestic violence escalate until the victim is murdered. If VAWA is allowed to lapse, it could have an adverse impact on federal protections for domestic violence survivors. Some may argue that these issues are evidence that the bill is a “failure” and should be allowed to die, but VAWA is only a failure if no one makes an effort to continue the fight. It is imperative to continue fighting against domestic violence when it has been implicated in mass shootings, an issue that has plagued our country for months and a factor in the decision to include a clause about removing firearms from convicted abusers. It is imperative to continue fighting when domestic violence has been linked to suicide, which is one of the main factors in decreased life expectancy in the United States. When healthcare and global health initiatives in the United States have already faced severe funding cuts, VAWA needs to be reauthorized.

Domestic violence is a public health issue. It is a humanitarian issue. Most importantly, it is an issue that all of us should care about.